Governor Phil Murphy on Fintech in New Jersey

April 14, 2021 In a joint webinar between Choose New Jersey, FinTech Ireland, the New Jersey City University School of Business, and others, NJ Governor Phil Murphy kicked off the event by saying that his state’s object is nothing short of being the state of innovation, where new ventures can take shape, companies can expand, and people can raise a family.

In a joint webinar between Choose New Jersey, FinTech Ireland, the New Jersey City University School of Business, and others, NJ Governor Phil Murphy kicked off the event by saying that his state’s object is nothing short of being the state of innovation, where new ventures can take shape, companies can expand, and people can raise a family.

Murphy’s participation in Irish fintech collaboration was steeped in his commitment to international relations and business.

“The fintech business in particular is a big part of our economy,” Murphy said. “We’ve got proximity to New York City’s financial markets and as a result we’ve become sort of the perfect home for fintech companies. We have 145 fintech companies headquartered in New Jersey.”

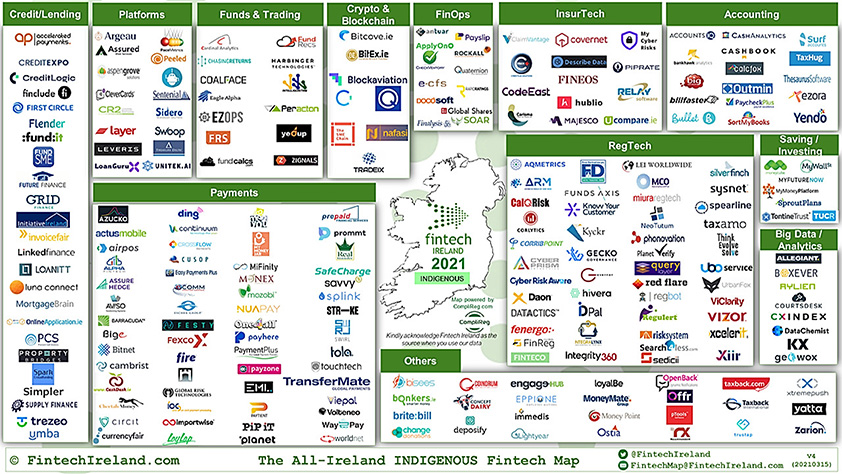

The island of Ireland, by comparison, is home to nearly 250 indigenous fintech companies, according to the latest Fintech Ireland map. Recently, Irish fintech companies ranked the United States and Canada as their #1 priority region for expansion.

New Jersey is hoping to benefit from transatlantic opportunities this might present.

“There’s no better place in America than to plant your flag here in New Jersey,” Murphy said. “To those who are considering [it], it’ll be the best decision you ever make.”

The Governor also revealed that his family is descended from Donoughmore, County Cork and that he hopes to make a state trip to the republic soon.

Ireland’s Fintech Industry May Be Coming to North America

March 16, 2021 Americans asked to name an Irish fintech company often say Stripe, the company founded by two Ireland-born brothers that is dual headquartered in San Francisco and Dublin. Recently valued at $95 billion, its financial backers include Sequoia Capital and the Irish government via the National Treasury Management Agency.

Americans asked to name an Irish fintech company often say Stripe, the company founded by two Ireland-born brothers that is dual headquartered in San Francisco and Dublin. Recently valued at $95 billion, its financial backers include Sequoia Capital and the Irish government via the National Treasury Management Agency.

Stripe’s Irish roots may not be a one-off. Though the Republic’s entire population (4.9M) is less than that of New York City (8.7M), it is home to nearly 250 indigenous fintech companies, dozens of which offer lending and payment products, according to the latest Fintech Ireland map. And many have expansion plans in the works.

Despite the close proximity to the UK, the United States and Canada tied for the #1 priority region that homegrown Irish fintech companies said they want to expand to, according to Fintech Ireland’s industry survey. The UK came in 2nd. The majority of Irish fintech companies actually said they prioritized expansion plans for the US and Canada even over expansion in their home country.

A flight from New York to Dublin can be shorter than a flight from New York to San Francisco and Ireland’s primary language is English. 7,000 people work in fintech in Ireland, the bulk of which are based in Dublin.

AltFinanceDaily evaluated the market in-person during the Fall of 2019 and determined that there are many cultural and operational similarities to the US. A follow-up piece in May 2020 captured how the industry there was faring through the Covid pandemic.

The Roosevelt Hotel is Closing Permanently Due to Pandemic Losses

October 13, 2020 After nearly a century of quintessential Manhatten hospitality, the Roosevelt Hotel is closing by the end of the month, sources say. A relic of classic New York that survived the Great Depression, WWII, and Broker Fair 2019, the hotel is officially shutting down for good after suffering pandemic related losses, a spokesperson said.

After nearly a century of quintessential Manhatten hospitality, the Roosevelt Hotel is closing by the end of the month, sources say. A relic of classic New York that survived the Great Depression, WWII, and Broker Fair 2019, the hotel is officially shutting down for good after suffering pandemic related losses, a spokesperson said.

“Due to the current, unprecedented environment and the continued uncertain impact from COVID-19, the owners of The Roosevelt Hotel have made the difficult decision to close the hotel, and the associates were notified this week,” the Spokesperson told CNN reporters Friday. “The iconic hotel, along with most of New York City, has experienced very low demand, and as a result, the hotel will cease operations before the end of the year. There are currently no plans for the building beyond the scheduled closing.”

The hotel will be added to the growing list of staple New York City businesses that have closed as a result of COVID. The Roosevelt was named and built to honor the United States’ 26th president and it opened its doors on September 22, 1924. Constructed during Prohibition, the building began the modern trend of featuring designer store windows on the street front.

Appearing as a backdrop for dozens of Hollywood blockbusters like Boiler Room, Malcolm X, and The Irishman, the hotel was iconic. The New Year’s Eve tradition of singing “Auld Lang Syne” was born at the Roosevelt in 1929 when Guy Lombardo and his orchestra broadcast the song live over the radio.

Appearing as a backdrop for dozens of Hollywood blockbusters like Boiler Room, Malcolm X, and The Irishman, the hotel was iconic. The New Year’s Eve tradition of singing “Auld Lang Syne” was born at the Roosevelt in 1929 when Guy Lombardo and his orchestra broadcast the song live over the radio.

The building was purchased by the limited investment branch of Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) in 1999.

In July, government officials and PIA executives debated the hotel’s future, some hoping rumors that President Trump would purchase the property were true. The initial plan was to sell or renovate the city block to create office space, thought to be far more lucrative than the hotel business in 2019. Work-from-home orders threw a wrench into the cogs, and the hotel kept losing money: no one wanted the traditional New York experience during a pandemic.

Posting a loss during this year has become expected of the hospitality industry. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, hospitality lost 7.5 million jobs due to shutdowns and travel restrictions in April. CNN reported that only half as many jobs had been added back. In September, NYC hotels were below 40% occupancy.

Posting a loss during this year has become expected of the hospitality industry. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, hospitality lost 7.5 million jobs due to shutdowns and travel restrictions in April. CNN reported that only half as many jobs had been added back. In September, NYC hotels were below 40% occupancy.

The decision to ultimately close The Roosevelt might also come from trouble in PIA’s airline business. After the crash of PIA flight 8303 that killed 97 people in Havelian, Pakistan, European and US regulators banned flights from PIA for six months. After the crash, nearly one-third of airplane licenses in Pakistan were found to be fraudulent or forged, further straining the organization’s ability to recover.

Though this may have contributed to The Roosevelt’s closure, the pandemic sealed the deal. According to a study by the American Hotel & Lodging Association, New York has 2,336 hotels statewide that have lost 43,014 jobs this year.

Without further congressional aid, 1,565 hotels might close: the AHLA found that 74% of overall US hotels say more layoffs are coming if the industry doesn’t get additional federal assistance. But successful talks for more aid in the House and Senate are increasingly unlikely due to this election year’s heightened partisanship.

Without further congressional aid, 1,565 hotels might close: the AHLA found that 74% of overall US hotels say more layoffs are coming if the industry doesn’t get additional federal assistance. But successful talks for more aid in the House and Senate are increasingly unlikely due to this election year’s heightened partisanship.

NYC is losing yet another historical business, as the way of life and all things we have come to expect from the big apple struggle to survive. As a destination venue, The Roosevelt was also dear to AltFinanceDaily. It was the home of Broker Fair 2019, where Sean Murray spoke in the same ballroom that Michel Douglas (as Gorden Gekko) made the famous “Greed is Good” speech as part of the 1987 film Wall Street. Murray made a similar speech but rewrote it to fit the industry that had gathered. “Funding small business, for lack of a better phrase, is good,” he said on stage to an audience of 700 people.

Unfortunately, it was The Roosevelt that ultimately needed funding and didn’t get it.

Ireland’s Alternative Finance Industry and the Coronavirus

May 18, 2020 As the effects of the coronavirus continue to slow down the American economy, around the world, many countries remain in lockdown, with their businesses having been halted. Be it to the north, south, east, or west, of the United States, the results are the same: money has stopped flowing. As such, we took the opportunity to follow up with some of the businesses that featured in our coverage of alternative finance in Ireland last Fall, hoping to see what differed and what was the same in their responses to the pandemic.

As the effects of the coronavirus continue to slow down the American economy, around the world, many countries remain in lockdown, with their businesses having been halted. Be it to the north, south, east, or west, of the United States, the results are the same: money has stopped flowing. As such, we took the opportunity to follow up with some of the businesses that featured in our coverage of alternative finance in Ireland last Fall, hoping to see what differed and what was the same in their responses to the pandemic.

Despite differing in size and range of variety when compared to their North American counterparts, the Irish alternative finance and fintech industries have largely felt the same impacts from covid-19. Certain funders have stopped operations, others have become very cautious, and just like here, some businesses have turned to the government for help.

LEO, or Local Enterprise Offices, is an advisory network for small and medium-sized businesses, which provide guidance as well as offer capital. The Irish government has pointed to these as the point of contact for small businesses owners, with LEO providing microfinance loans of up €50,000. This figure being upped from the pre-coronavirus maximum of €25,000.

Rupert Hogan, the Managing Director of brokering company BusinessLoans.ie, explained that some businesses would be better going with LEO over banks and even some non-banks. Noting that non-bank lenders can’t compete with the rates offered by LEO and, just like in the US, banks can’t act with the speed that these business owners need.

Hogan, who describes the current situation as “The Great Lockdown,” said that banks “aren’t too helpful, even in the good times,” due to the high rejection rates that SMEs experience when looking for loans. In regards to merchant cash advances, he’s expecting, when the MCA companies reopen, that they’ll be funding at reduced rates, some doing as much as 50% less than their pre-coronavirus amounts.

Hogan, who describes the current situation as “The Great Lockdown,” said that banks “aren’t too helpful, even in the good times,” due to the high rejection rates that SMEs experience when looking for loans. In regards to merchant cash advances, he’s expecting, when the MCA companies reopen, that they’ll be funding at reduced rates, some doing as much as 50% less than their pre-coronavirus amounts.

Jaime Heaslip, Head of Brand Marketing at the MCA company Flender, explained that before the virus, the company was experiencing a period of productivity, with lending activity and amounts deposited being up from previous years. And despite the virus disrupting commerce, the former international rugby player noted that business owners are still coming to Flender for funds.

“We provide flexibility for people, there’s a lot of people coming to us to get contingency funds together,” he said over a phone call, commenting that as well as this, many businesses are looking for financing to move their operations online. “We’re trying to help SMEs get through this and provide as much help as possible.”

Beyond merchant cash advances, business continues to run, says Spark Crowdfunding’s Chris Burge. Being an investment platform, Spark is still active with businesses looking to get off the ground.

“We’ve actually found that we’ve still got a large amount of inquiries coming through,” the CEO and Co-Founder said. “Our pipeline of companies wanting to go onto the platform is very strong, and we’ve been engaging with them all and they’re very keen. They all need money, which, of course, hasn’t changed from before there was a crisis. And they still are needing money, they need that to expand as opposed to survive.”

When asked about changes made because of covid-19, Burge explained that their investor evenings have been disrupted. Previously an opportunity for the investors and investees on the digital platform to meet up personally and pitch each other, these 100-person gatherings are no longer an option. Instead, virtual webinars and assemblies are what Spark has started using to keep up communication between parties.

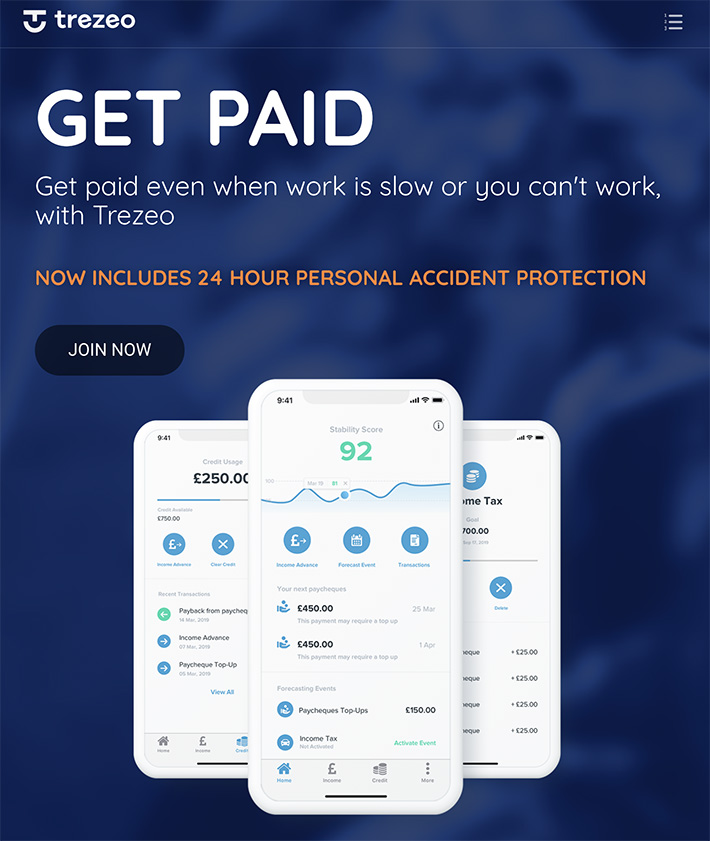

And on the subject of fundraising, Trezeo’s Garrett Cassidy said that it has become a nightmare under the pandemic. Disrupted communication channels and the inability to pitch to someone in the same room as you have been hurdles, but besides that, Cassidy assured me that Trezeo is still going strong.

Offering payment structures and benefit bundles to freelancers and the self-employed, Trezeo has seen some of its customer base drop off as unemployment sky-rocketed in the UK, its prime market. Despite this, as more and more people are beginning to go back to work, Cassidy says numbers are rising.

Offering payment structures and benefit bundles to freelancers and the self-employed, Trezeo has seen some of its customer base drop off as unemployment sky-rocketed in the UK, its prime market. Despite this, as more and more people are beginning to go back to work, Cassidy says numbers are rising.

“Now we’re starting to see earnings pick back up again, some of them were the ones who were off work who are now coming back to work. So it’s been interesting watching that but the reality is that they’re also scared. They’re out working every day delivering parcels or food, depending on which, and just working really hard. It’s the most important ones who are paid the least and that have the least protection.”

Looking ahead, Trezeo has been working with the UK’s Labour Exchange to establish a new program that would see the creation of channels to help pre-qualify workers for certain positions. These workers would be pooled, and employers would be able to choose from them, streamlining the hiring process for both sides.

“They need money in their pockets, somehow, quickly,” Cassidy said of workers, whether that be by returning to work safely, or through some government assistance program, the CEO is adamant that people need to stay solvent.

Altogether, Ireland’s alternative finance industry, like others the world over, has been hit hard by the coronavirus’s economic effects. With the country’s phased lifting of the lockdown being plotted out over the course of the summer, the island nation may not see as quick a return to commerce as certain American states, but its fintechs and non-banks hope to stick around, by hook or by crook, as the Irish say, by any means possible.

Flender Makes BIG Mark in Ireland’s SME Lending Market

November 26, 2019 Ireland can seem like a small place, so much so that on my way to meeting with Colin Canny, Flender’s Head of Partnerships, I quite literally bumped into Flender’s co-founder & CEO Kristjan Koik who was walking through Dublin’s Silicon Docks. I recognized Koik from the who’s who catalogue of executives I had compiled before traveling abroad to explore the Irish fintech scene. He was cordial and polite. And yet through his demeanor I sensed there was more, that there was a story to be told even if it was not ready to be shared.

Ireland can seem like a small place, so much so that on my way to meeting with Colin Canny, Flender’s Head of Partnerships, I quite literally bumped into Flender’s co-founder & CEO Kristjan Koik who was walking through Dublin’s Silicon Docks. I recognized Koik from the who’s who catalogue of executives I had compiled before traveling abroad to explore the Irish fintech scene. He was cordial and polite. And yet through his demeanor I sensed there was more, that there was a story to be told even if it was not ready to be shared.

The following month Flender would reveal remarkable news, a new €75 million funding line, bringing their total to €109 million raised since the company’s founding in 2015. The company is backed by Eiffel Investment Group, Enterprise Ireland, entrepreneur Mark Roden and former Ireland rugby player Jamie Heaslip.

This large amount of funding, even by UK or US standards, makes Flender stand out, and so when I finally meet with Canny on that warm Fall day in September, I’m pretty thankful he afforded me the time.

Flender, Canny explains, is derived from Flexible Lender. The pamphlet he produces and hands to me says that their idea is simple, to provide businesses with the funding they need and ensure the application process is fast, easy, and transparent.

Application details for products like term loans and merchant cash advances require the usual stips like historical bank statements, a profit & loss statement, and a balance sheet. But there’s also a section quintessentially Irish, that is that it can be beneficial to submit your last 2 years herd numbers if you’re a farmer, complete with your last 12 months Milk Reports and property acreage figure.

Canny explains that Flender is not a high-risk fall-back lender, but rather the opposite. “Our credit process is extremely tight,” he says, “in line with banks.” And with good rationale, seeing that the company is still somewhat reliant on a peer-to-peer funding model. More than half of individual peers on the platform are Irish but Canny says that it’s not unusual for non-residents including Americans to lend on the platform as well.

Canny explains that Flender is not a high-risk fall-back lender, but rather the opposite. “Our credit process is extremely tight,” he says, “in line with banks.” And with good rationale, seeing that the company is still somewhat reliant on a peer-to-peer funding model. More than half of individual peers on the platform are Irish but Canny says that it’s not unusual for non-residents including Americans to lend on the platform as well.

Canny says the Irish market is very “community based.” The transparency of the marketplace aligns with that characterization. Like other peer-to-peer small business lenders in Ireland, borrower identity is publicly accessible on the platform, as are the terms of the loan. Anyone can view the business name of a prospective borrower on the website, the address, a bio, and even their “story.”

Flender taps several marketing channels like Google Adwords, radio, direct sales, and even brokers. Canny says they generate an underwriting decision in as quick as 4-6 hours and fund a business in as little as 24 hours. Borrowers like the product so much that many renew. Seventy percent of the SMEs in the country are peer-to-peer bankable, Canny explains, creating a wide playing field to target.

Meawnwhile, CEO Kristjan Koik told the Irish Times that the top 3 banks in Ireland have 92 percent of the SME lending marketshare so there is still a ton of opportunity for non-banks like Flender to grab hold of.

As for how the massive credit line impacts them going forward? Koik told the Times that they would be cutting interest rates by up to 1 percent across their various loan products. Interest rates now start as low as 6.45% and terms range up to 36 months.

As Canny and I part ways I present one final question, will Flender be expanding abroad? I get no definitive answer. He was cordial and polite, and yet I sensed through his demeanor that there was more, perhaps even a story in the works that was not yet ready to be shared.

The FTC Wants To Police Small Business Finance

October 22, 2019 On May 23, the Federal Trade Commission launched an investigation into unfair or deceptive practices in the small business financing industry, including by merchant cash advance providers.

On May 23, the Federal Trade Commission launched an investigation into unfair or deceptive practices in the small business financing industry, including by merchant cash advance providers.

The agency is looking into, among other things, whether both financial technology companies and merchant cash advance firms are making misrepresentations in their marketing and advertising to small businesses, whether they employ brokers and lead-generators who make false and misleading claims, and whether they engage in legal chicanery and misconduct in structuring contracts and debt-servicing.

Evan Zullow, senior attorney at the FTC’s consumer protection division, told AltFinanceDaily that the FTC is, moreover, investigating whether fintechs and MCAs employ “problematic,” “egregious” and “abusive” tactics in collecting debts. He cited such bullying actions as “making false threats of the consequences of not paying a debt,” as well as pressuring debtors with warnings that they could face jail time, that authorities would be notified of their “criminal” behavior, contacting third-parties like employers, colleagues, or family members, and even issuing physical threats.

“Broadly,” Zullow said in a telephone interview, “our work and authority reaches the full life cycle of the financing arrangement.” He added: “We’re looking closely at the conduct (of firms) in this industry and, if there’s unlawful conduct, we’ll take law enforcement action.”

Zullow declined to identify any targets of the FTC inquiry. “I can’t comment on nonpublic investigative work,” he said.

The FTC investigation is one of several regulatory, legislative and law enforcement actions facing the merchant cash advance industry, which was triggered by a Bloomberg exposé last winter alleging sharp practices by some MCA firms.

The FTC investigation is one of several regulatory, legislative and law enforcement actions facing the merchant cash advance industry, which was triggered by a Bloomberg exposé last winter alleging sharp practices by some MCA firms.

The Bloomberg series told of high-cost financings, of MCA firms’ draining debtors’ bank accounts, and of controversial collections practices in which debtors signed contracts that included “confessions of judgment.”

The FTC long ago outlawed the use of COJs in consumer loan contracts and several states have banned their use in commercial transactions. In September, Governor Andrew Cuomo signed legislation prohibiting the use of COJs in New York State courts for out-of-state residents. And there is a bipartisan bill pending in the U.S. Senate authored by Florida Republican Marco Rubio and Ohio Democrat Sherrod Brown to outlaw COJs nationwide.

Mark Dabertin, a senior attorney at Pepper Hamilton, described the FTC’s investigation of small business financing as a “significant development.” But he also said that the agency’s “expansive reading of the FTC Act arguably presents the bigger news.” Writing in a legal memorandum to clients, Dabertin added: “It opens the door to introducing federal consumer protection laws into all manner of business-to-business conduct.”

FTC attorney Zullow told AltFinanceDaily, “We don’t think it’s new or that we’re in uncharted waters.”

The FTC inquiry into alternative small business financing is not the only investigation into the MCA industry. Citing unnamed sources, The Washington Post reported in June that the Manhattan district attorney is pursuing a criminal investigation of “a group of cash advance executives” and that the New York State attorney general’s office is conducting a separate civil probe.

The FTC’s investigation follows hard on the heels of a May 8 forum on small business financing. Labeled “Strictly Business,” the proceedings commenced with a brief address by FTC Commissioner Rohit Chopra, who paid homage to the vital role that small business plays in the U.S. economy. “Hard work and the creativity of entrepreneurs and new small businesses helped us grow,” he said.

But he expressed concern that entrepreneurship and small business formation in the U.S. was in decline. According to census data analyzed by the Kaufmann Foundation and the Brookings Institution, the commissioner noted, the number of new companies as a share of U.S. businesses has declined by 44 percent from 1978 to 2012.

“It’s getting harder and harder for entrepreneurs to launch new businesses,” Chopra declared. “Since the 1980s, new business formation began its long steady decline. A decade ago births of new firms started to be eclipsed by deaths of firms.”

Chopra singled out one-sided, unjust contracts as a particularly concerning phenomenon. “One of the most powerful weapons wielded by firms over new businesses is the take-it-or-leave-it contract,” he said, adding: “Contracts are ways that we put promises on paper. When it comes to commerce, arm’s length dealing codified through contracts is a prerequisite for prosperity. “But when a market structure requires small businesses to be dependent on a small set of dominant firms — or firms that don’t engage in scrupulous business practices — these incumbents can impose contract terms that cement dominance, extract rents, and make it harder for new businesses to emerge and thrive.”

As the panel discussions unfolded, representatives of the financial technology industry (Kabbage, Square Capital and the Electronic Transactions Association) as well as executives in the merchant cash advance industry (Kapitus, Everest Business Financing, and United Capital Source) sought to emphasize the beneficial role that alternative commercial financiers were playing in fostering the growth of small businesses by filling a void left by banks.

The fintechs went first. In general, they stressed the speed and convenience of their loans and lines of credit, and the pioneering innovations in technology that allowed them to do deeper dives into companies seeking credit, and to tailor their products to the borrower’s needs. Panelists cited the “SMART Box” devised by Kabbage and OnDeck as examples of transparency. (Accompanying those companies’ loan offers, the SMART Box is modeled on the uniform terms contained in credit card offerings, which are mandated by the Truth in Lending Act. TILA does not pertain to commercial debt transactions.)

Sam Taussig, head of global policy at Kabbage, explained that his company typically provides loans to borrowers with five to seven employees — “truly Main Street American small businesses” — that are seeking out “project-based financing” or “working capital.”

Sam Taussig, head of global policy at Kabbage, explained that his company typically provides loans to borrowers with five to seven employees — “truly Main Street American small businesses” — that are seeking out “project-based financing” or “working capital.”

“The average small business according to our research only has about 27 days of cash flow on hand,” Taussig told the fintech panel, FTC moderators and audience members. “So if you as a small business owner need to seize an opportunity to expand your revenue or (have) a one-off event — such as the freezer in your ice cream store breaks — it’s very difficult to access that capital quickly to get back to business or grow your business.”

Taussig contrasted the purpose of a commercial loan with consumer loans taken out to consolidate existing debt or purchase a consumer product that’s “a depreciating asset.” Fintechs, which typically supply lightning-quick loans to entrepreneurs to purchase equipment, meet payrolls, or build inventory, should be judged by a different standard.

A florist needs to purchase roses and carnations for Mother’s Day, an ice-cream store must replenish inventory over the summer, an Irish pub has to stock up on beer and add bartenders at St. Patrick’s Day.

The session was a snapshot of not just the fintech industry but of the state of small business. Lewis Goodwin, the head of banking services at Square Capital, noted that small businesses account for 48% of the U.S. workforce. Yet, he said, Square’s surveys show that 70% of them “are not able to get what they want” when they seek financing.

Square, he said, has made 700,000 loans for $4.5 billion in just the past few years, the platform’s average loan is between $6,000 and $7,000, and it never charges borrowers more than 15% of a business’s daily receipts. The No. 1 alternative for small businesses in need of capital is “friends and family,” Goodwin said, “and that’s a tough bank to go back to.”

Panelist Gwendy Brown, vice-president of research and policy at the Opportunity Fund, a non-profit microfinance organization, provided the fintechs with their most rocky moment when she declared that small businesses turning up at her fund were typically paying an annual percentage rate of 94 percent for fintech loans. And while most small business owners were knowledgeable about their businesses — the florists “know flowers in and out,” for example — they are often bewildered by the “landscape” of financial product offerings.

Panelist Gwendy Brown, vice-president of research and policy at the Opportunity Fund, a non-profit microfinance organization, provided the fintechs with their most rocky moment when she declared that small businesses turning up at her fund were typically paying an annual percentage rate of 94 percent for fintech loans. And while most small business owners were knowledgeable about their businesses — the florists “know flowers in and out,” for example — they are often bewildered by the “landscape” of financial product offerings.

“Sophistication as a business owner,” Brown said, “does not necessarily equate into sophistication in being able to assess finance options.”

Panelist Claire Kramer Mills, vice-president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, reported that the country’s banks have made a dramatic exit from small business lending over the past ten years. A graphic would show that bank loans of more than $1 million have risen dramatically over the past decade but, she said, “When you look at the small loans, they’ve remained relatively flat and are not back to pre-crisis levels.”

Mills also said that 50% of small businesses in the Federal Reserve’s surveys “tell us that they have a funding shortfall of some sort or another. It’s more stark when you look at women-owned business, black or African-American owned businesses, and Latino-owned businesses.”

On the merchant cash advance panel there was less opportunity to dazzle the regulators and audience members with accounts of state-of-the-art technology and the ability to aggregate mountains of data to make online loans in as few as seven minutes, as Kabbage’s Taussig noted the fintech is wont to do.

Instead, industry panelists endeavored to explain to an audience — which included skeptical regulators, journalists, lawyers and critics — the precarious, high-risk nature of an MCA or factoring product, how it differs from a loan, and the upside to a merchant opting for a cash advance. (To their credit, one attendee told AltFinanceDaily, the audience also included members of the MCA industry interested in compliance with federal law.)

Instead, industry panelists endeavored to explain to an audience — which included skeptical regulators, journalists, lawyers and critics — the precarious, high-risk nature of an MCA or factoring product, how it differs from a loan, and the upside to a merchant opting for a cash advance. (To their credit, one attendee told AltFinanceDaily, the audience also included members of the MCA industry interested in compliance with federal law.)

A merchant cash advance is “a purchase of future receipts,” Kate Fisher, an attorney at Hudson Cook in Baltimore, explained. “The business promises to deliver a percentage of its revenue only to the extent as that revenue is created. If sales go down,” she explained, “then the business has a contractual right to pay less. If sales go up, the business may have to pay more.”

As for the major difference between a loan and a merchant cash advance: the borrower promises to repay the lender for the loan, Fisher noted, but for a cash advance “there’s no absolute obligation to repay.”

Scott Crockett, chief executive at Everest Business Funding, related two anecdotes, both involving cash advances to seasonal businesses. In the first instance, a summer resort in Georgia relied on Everest’s cash advances to tide it over during the off-season.

When the resort owner didn’t call back after two seasonal advances, Crockett said, Everest wanted to know the reason. The answer? The resort had been sold to Marriott Corporation. Thanking Everest, Crockett said, the former resort-owners reported that without the MCA, he would likely have sold off a share of his business to a private equity fund or an investor.

By providing a cash advance Everest acted “more like a temporary equity partner,” Crockett remarked.

In the second instance, a restaurant in the Florida Keys that relied on a cash advance from Everest to get through the slow summer season was destroyed by Hurricane Irma. “Thank God no one was hurt,” Crockett said, “but the business owner didn’t owe us anything. We had purchased future revenues that never materialized.”

The outsized risk borne by the MCA industry is not confined entirely to the firm making the advance, asserted Jared Weitz, chief executive at United Capital Service, a consultancy and broker based in Great Neck, N.Y. It also extends to the broker. Weitz reported that a big difference between the MCA industry and other funding sources, such as a bank loan backed by the Small Business Administration, is that ”you are responsible to give that commission back if that merchant does not perform or goes into an actual default up to 90 days in.

“I think that’s important,” Weitz added, “because on (both) the broker side and on the funding side, we really are taking a ride with the merchant to make sure that the business succeeds.”

FTC’s panel moderators prodded the MCA firms to describe a typical factor rate. Jesse Carlson, senior vice-president and general counsel at Kapitus, asserted that the factor rate can vary, but did not provide a rate.

FTC’s panel moderators prodded the MCA firms to describe a typical factor rate. Jesse Carlson, senior vice-president and general counsel at Kapitus, asserted that the factor rate can vary, but did not provide a rate.

“Our average financing is approximately $50,000, it’s approximately 11-12 months,” he said. “On a $50,000 funding we would be purchasing $65,000 of future revenue of that business.”

The FTC moderator asked how that financing arrangement compared with a “typical” annual percentage rate for a small business financing loan and whether businesses “understand the difference.”

Carlson replied: “There is no interest rate and there is no APR. There is no set repayment period, so there is no term.” He added: “We provide (the) total cost in a very clear disclosure on the first page of all of our contracts.”

Ami Kassar, founder and chief executive of Multifunding, a loan broker that does 70% of its work with the Small Business Administration, emerged as the panelist most critical of the MCA industry. If a small business owner takes an advance of $50,000, Kassar said, the advance is “often quoted as a factor rate of 20%. The merchant thinks about that as a 20% rate. But on a six-month payback, it’s closer to 60-65%.”

He asserted that small businesses would do better to borrow the same amount of money using an SBA loan, pay 8 1/4 percent and take 10 years to pay back. It would take more effort and the wait might be longer, but “the impact on their cash flow is dramatic” — $600 per month versus $600 a day, he said — “compared to some of these other solutions.”

Kassar warned about “enticing” offers from MCA firms on the Internet, particularly for a business owner in a bind. “If you jump on that train and take a short-term amortization, oftentimes the cash flow pressure that creates forces you into a cycle of short-term renewals. As your situation gets tougher and tougher, you get into situations of stacking and stacking.”

On a final panel on, among other matters, whether there is uniformity in the commercial funding business, panelists described a massive muddle of financial products.

Barbara Lipman: project manager in the division of community affairs with the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, said that the central bank rounded up small businesses to do some mystery shopping. The cohort — small businesses that employ fewer than 20 employees and had less than $2 million in revenues — pretended to shop for credit online.

As they sought out information about costs and terms and what the application process was like, she said, “They’re telling us that it’s very difficult to find even some basic information. Some of the lenders are very explicit about costs and fees. Others however require a visitor to go to the website to enter business and personal information before finding even the basics about the products.” That experience, Lipman said, was “problematic.”

She also said that, once they were identified as prospective borrowers on the Internet, the Fed’s shoppers were barraged with a ceaseless spate of online credit offers.

John Arensmeyer, chief executive at Small Business Majority, an advocacy organization, called for greater consistency and transparency in the marketplace. “We hear all the time, ‘Gee, why do we need to worry about this? These are business people,’” he said. “The reality is that unless a business is large enough to have a controller or head of accounting, they are no more sophisticated than the average consumer.

“Even about the question of whether a merchant cash advance is a loan or not,” Arensmeyer added. “To the average small business owner everything is a loan. These legal distinctions are meaningless. It’s pretty much the Wild West.”

In the aftermath of the forum, the question now is: What is the FTC likely to do?

In the aftermath of the forum, the question now is: What is the FTC likely to do?

Zullow, the FTC attorney, referred AltFinanceDaily to several recent cases — including actions against Avant and SoFi — in which the agency sanctioned online lenders that engaged in unfair or deceptive practices, or misrepresented their products to consumers.

These included a $3.85 million settlement in April, 2019, with Avant, an online lending company. The FTC had charged that the fintech had made “unauthorized charges on consumers’ accounts” and “unlawfully required consumers to consent to automatic payments from their bank accounts,” the agency said in a statement.

In the settlement with SoFi, the FTC alleged that the online lender, “made prominent false statements about loan refinancing savings in television, print, and internet advertisements.” Under the final order, “SoFi is prohibited from misrepresenting to consumers how much money consumers will save,” according to an FTC press release.

But these are traditional actions against consumer lenders. A more relevant FTC action, says Pepper Hamilton attorney Dabertin, was the FTC’s “Operation Main Street,” a major enforcement action taken in July, 2018 when the agency joined forces with a dozen law enforcement partners to bring civil and criminal charges against 24 alleged scam artists charged with bilking U.S. small businesses for more than $290 million.

In the multi-pronged campaign, which Zullow also cited, the FTC collaborated with two U.S. attorneys’ offices, the attorneys general of eight states, the U.S. Postal Inspection Service, and the Better Business Bureau. According to the FTC, the strike force took action against six types of fraudulent schemes, including:

- Unordered merchandise scams in which the defendants charged consumers for toner, light bulbs, cleaner and other office supplies that they never ordered;

- Imposter scams in which the defendants use deceptive tactics, such as claiming an affiliation with a government or private entity, to trick consumers into paying for corporate materials, filings, registrations, or fees;

- Scams involving unsolicited faxes or robocalls offering business loans and vacation packages.

If there remains any question about whether the FTC believes itself constrained from acting on behalf of small businesses as well as consumers, consider the closing remarks at the May forum made by Andrew Smith, director of the agency’s bureau of consumer protection.

“(O)ur organic statute, the FTC Act, allows us to address unfair and deceptive practices even with respect to businesses,” Smith declared, “And I want to make clear that we believe strongly in the importance of small businesses to the economy, the importance of loans and financing to the economy.

Smith asserted that the agency could be casting a wide net. “The FTC Act gives us broad authority to stop deceptive and unfair practices by nonbank lenders, marketers, brokers, ISOs, servicers, lead generators and collectors.”

As fintechs and MCAs, in particular, await forthcoming actions by the commission, their membership should take pains to comport themselves ethically and responsibly, counsels Hudson Cook attorney Fisher. “I don’t think businesses should be nervous,” she says, “but they should be motivated to improve compliance with the law.”

She recommends that companies make certain that they have a robust vendor-management policy in place, and that they review contracts with ISOs. Companies should also ensure that they have the ability to audit ISOs and monitor any complaints. “Take them seriously and respond,” Fisher says.

Companies would also do well to review advertising on their websites to ascertain that claims are not deceptive, and see to it that customer service and collections are “done in a way that is fair and not deceptive,” she says, adding of the FTC investigation: “This is a wake-up call.”

Salaries For All, Even For Gig Workers

October 16, 2019 “If we don’t solve the problems, there’s just a nightmare coming.”

“If we don’t solve the problems, there’s just a nightmare coming.”

This is how Trezeo’s CEO and Co-founder Garrett Cassidy views the work that he and his company are doing. Created in 2016 with the aim to provide support to self-employed people via income smoothing, Trezeo offers workers whose income streams may be irregular the opportunity to have structured and regular paydays similar to those who earn a salary. And with the number of self-employed in the UK currently at approximately five million, as well as projections showing that the majority of US workers will be freelancers by 2027, the company sees its efforts as essential to solving future problems. “There’s a lot of noise around the gig economy,” Cassidy asserted. “But the world is moving that way and we’re very much like ‘that’s fine, you can push back all you want, it’s going that way and we need to create the services that will work for these people.’”

The way it works is that Trezeo serves as an alternative lender, offering regularly paid funds to the customer’s account in exchange for their income that comes in at a later date. A major difference between it and other alternative lenders though is that Trezeo does not charge interest on these advances, instead collecting its revenue from a weekly membership fee of £3.

“We want to allow them to build their own financial resilience and also start looking a bit more useful for traditional financial institutions to engage with,” Cassidy explained. “Our ultimate vision is if you choose to be freelance or self-employed why should you cut yourself off from financial security, why should you trade flexibility for security, and, therefore, that’s the whole ethos of the income smoothing.”

Beyond this service Trezeo has plans to include additional features, such as an income verification system that would help workers be approved for large loans, like mortgages, from banks; as well as an opt-in pension, where instead of being committed to paying a fixed amount each pay cheque, customers could pay 5% of their total income for that period. Trezeo has already gotten the ball rolling with such expansions with the release of its personal accident and disabilities insurance, which covers customers for £300 per week for six months in the case that they are unable to work.

While it may sound as if self-employed and freelance workers are signing up for Trezeo to be their surrogate employer, Cassidy is quick to emphasize that this is instead a new system built to reflect the opportunities presented by technology, distant but reminiscent of the employment structures that came before.

“We’re trying to recreate [the structure] in a way so that a self-employed person controls it and over time can decide what they want … We’re not trying to make them employees, we’re very careful about that, but we’re trying to make it an employee-like experience for them so that they can very easily manage their finances and see them like an employee traditionally would … Platforms are making it easier for people to take the choice of flexibility.”

Speaking to Cassidy in Trezeo’s Irish office in the National Digital Research Centre, an early stage investor in tech companies, we’re snuggly located close by St. James’s Gate Brewery, where the cobbled streets are filled with the nutty and barley-laden smell of Guinness being brewed.

From here is where the development team operates, whereas the risk, sales, and marketing teams work from their London office, with the UK being their only market at this time. However Cassidy assured me that the company is looking interestedly abroad to Western Europe and America with plans to expand.

“This is a very big niche globally,” Cassidy remarked. “And as we’ve gone along, we’ve realized how much of an impact we can have.”

How Ireland’s Spark Crowdfunding Got its Start

October 5, 2019 “We’ve not invented anything new,” Chris Burge, CEO of Spark Crowdfunding, tells me. “We saw the rise of crowdfunding in Europe, the states, and the world and we thought, ‘well why doesn’t Ireland have one?’”

“We’ve not invented anything new,” Chris Burge, CEO of Spark Crowdfunding, tells me. “We saw the rise of crowdfunding in Europe, the states, and the world and we thought, ‘well why doesn’t Ireland have one?’”

We’re in the lobby of a Dublin hotel drinking coffee, right around the corner from Spark’s offices on South William Street. There are at least three other professional meetings going on over variations of hot drinks, the room serving as a haven from the uniquely cold-yet-clammy weather outside.

Burge tells me about how he came to be in alternative finance. An engineer by trade, Burge entered the field after both him and his business partner had found the traditional process of investing to be wanting. “Both of us had invested in the past and had found it cumbersome, long-winded, and expensive,” leading them to explore more accessible, less unwieldy options.

Thus, from such a hole in the market sprung Spark Crowdfunding. Offering equity investment options from as low as €100, Burge sought to streamline the investment by offering it via an online platform from which members can view pitch videos, pitch decks, and detailed documents.

Established in early 2018, the company saw its first big success in August of that year with Fleet, an Irish business that allows cars owners to rent their vehicles to the public from their driveways as well as gas stations. Asking for €275,000, Fleet received this and more, with the total amount invested reaching €385,000.

Established in early 2018, the company saw its first big success in August of that year with Fleet, an Irish business that allows cars owners to rent their vehicles to the public from their driveways as well as gas stations. Asking for €275,000, Fleet received this and more, with the total amount invested reaching €385,000.

Allowing for choice when deciding which investors to choose from and how much to take from who, Burge says that flexibility is key to their platform and likens it to Dragons’ Den with much more than five potential investors.

And with bank loans for small businesses becoming increasingly more difficult to access, Spark is positioned similarly to crowdfunding in the US. “Where a company would have previously gone to Allied Irish Bank or Bank of Ireland to borrow €100,000 in order to get their business off the ground, they’re now finding it very difficult and nigh impossible as well to get these loans, so we found that a lot of companies are coming to us to do this.” In addition to such an investment, startups in Ireland may receive extra funding from Enterprise Ireland, a government organization that provides aid to indigenous businesses and will match investments up to a point so long as the company meets certain requirements.

Accompany this with the lack of regulation in the crowdfunding space in Ireland and it would appear that the industry is set to expand.

And on the topic of expansion, Burge is keeping most of his cards to himself. “We know that Ireland is a small country compared to the rest of Europe, or compared to the rest of the world, so there’s a limited amount of stuff that we can do here, and so do we want to grow? Yes. Are we going to go to the states? Probably not. But the rest of Europe? Yes, absolutely. Have we picked out a few countries? Yes, we have.”